‘Knife’ comes out this month, the book in which he remembers how he was murdered but didn’t die.

Practically all of his books “are involved in controversy” – this is an essential condition for a great writer, and Salman Rushdie confirms the rule. ‘Midnight’s Children’ (1981) won the coveted Booker, one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the English language, but was widely criticized in India for the accusations it leaves here and there about the Gandhi clan. It is an extraordinary novel, following the life of Saleem Sinai, bald and deaf, who was born in the first hour of India’s independence, in 1947 (he tells the story of his generation to the great love of his life, Padma Mangrol) – and you can say It is a novel reminiscent of Latin American “magical realism”, full of humor (a lot) and poetry, fantastic characters and bizarre situations. This is followed by ‘Shame’ (1983), which was also a Booker finalist and received several awards – and which deals with Pakistan and the country’s political history. Five years later, in 1988, it was the turn of ‘The Satanic Verses’, when Salman Rushdie’s story changed radically. Not because it was an ‘extraordinarily’ better book than ‘Midnight’s Children’ (but it is), but because it not only provoked controversy – a word so worn out that today it doesn’t mean anything – it provoked a vast wave of protests, destruction, deaths, bomb attacks, diplomatic war and, in fact, the name of a writer being brought to the front pages around the world.

Ironies: the Iranian government had awarded the translation of ‘Shame’ published in Tehran two years earlier; Rushdie had supported Iran’s Islamic revolution in 1979 and had on several occasions attacked the US, “the policeman of the world”, which he had harshly criticized for the bombing of Tripoli, Libya, three years before Muammar Gaddafi joined the chorus of those who called for Rushdie’s death.

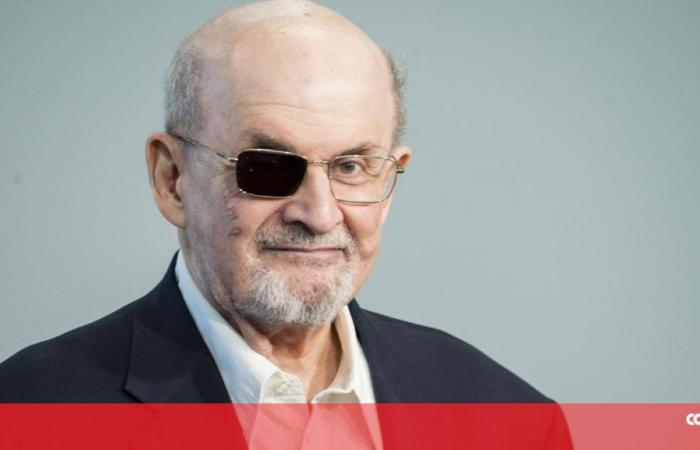

And why ask for the death of that 41-year-old man, with the appearance of an imp, who was born in Bombay in 1947, the son of a businessman with literary tastes and a teacher, who sent him to England in 1964, where he ended up graduating in History? at Cambridge University? Because, in the book, the Prophet, Muhammad, is attributed with the inclusion of a controversial mythical passage from the Koran, attributed to pagan goddesses. Muhammad (addressed as Mahound, considered derogatory) repented and withdrew it, but the mistake had been made. There is a list of small indignities (a prophet with dandruff, a naughty angel, the prophet’s wives named after prostitutes, etc.), but the fact is that one small incident was enough to set the world on fire. The book, published in 1988 in England and early 1989 in the US, provoked protest marches by radical Islamist organizations in England (including the local Islamic Students’ Association), who burned it in public. It is proven that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini never read more than two or three pages (his son confirms) before issuing a decree (a ‘fatwa’) condemning Rushdie to death and hellfire, with a reward of 6 million dollars for whoever carries out the sentence, which was renewed in 2005 (in a statement to pilgrims to Mecca) and in 2006, by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard – and the reward increased several times. In between, bookstores were looted, the offices of a New York newspaper were destroyed, and the Japanese translator was killed in 1991, ten days after the Italian translator was stabbed. In 2012, Rushdie published ‘Joseph Anton. A Memory’ (that was the name Salman Rushdie used while he lived in hiding and under police protection, with sporadic appearances), and the Iranian reward for his death soon increased in value. For another 10 years, Rushdie was a figure of American pop stardom, dated, appeared on television, gave conferences, came to Portugal, traveled – but the threat loomed, until, on August 12, 2022, someone executed her.Hadi Matar was 24 years old, born in California (the family has since returned to Lebanon, to Yaroun, an area controlled by the pro-Iranian Shiite militias of Hezbollah), lived in New Jersey and bought his ticket for the conference-interview he was going to have place in Chautauqua, a quiet, low-key place where writers, musicians and artists met. She stabbed him in the face, neck and abdomen. Rushdie, evacuated to a NY hospital, survived but lost an eye – in other words, he was murdered, but did not die. Matar’s parents in Lebanon wished him recovery and condemned Hadi.As for Rushdie, he has just published ‘Knife. Meditations Following a Murder Attempt’, which D. Quixote launches next month. In it, he tells how he began to see blood flowing and realized that someone was going to kill him. The threat was real.

Atiradiço & POP STAR

The poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, 46 years old, is the fifth marriage of Salman Rushdie, 76: “The woman who saved my life”, as she says in a recent interview (they married in 2021). Before that, Rushdie’s sentimental and marital life was a topic of conversation, a subject of press, accusations and recriminations, revenge and scandalous revelations. He went well with Clarisse Luard, whom he married in 1976 (and with whom he had a son, Zafar); the divorce took place in 1987, and Clarisse died of cancer in 1999. He had a bad relationship with the writer Marianne Wiggins, with whom he was married between 1988 and 1993, during the initial period of the Iranian fatwa; less badly with the author and editor Elizabeth West, between 1997 and 2004 (one son, Milan) and which corresponded to the period in which Rushdie went to live in New York; and it was turbulent and scandalous, with controversies and public accusations, which he maintained with the actress and model of Indian origin Pardma Lakshimi between 2004 and 2007 (she was 28 years old, he was 51). One of the regular occupations of the popular press, especially after his marriage to Lakshimi, was to follow Rushdie’s meetings and courtships in New York.

Cancellations and censorship

Khomeini’s fatwa condemning Salman Rushdie to death was issued on February 14, 1989, Valentine’s Day – the day before the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan was officially completed, a victory for the Islamic world. That same month, there were 80 bomb threats against American bookstores, with one even exploding in Berkeley, California. In England, the historic and famous Dillons, in London, was one of the targets of attacks that occurred in several cities, set on fire by Muslim leaders during their speeches in the most radical mosques. In the US, more than a third of bookstores did not sell ‘The Satanic Verses’, and in many of the others, the book was sold behind the counters and wrapped before being given to buyers. A ban on the sale of the novel was enacted in countries such as Kenya, Thailand, Indonesia, Pakistan, Singapore, India, Malaysia, Bangladesh, South Africa or Sri Lanka, among others – Venezuela followed the ban in 1989.