In a society in constant evolution, the concept of freedom resonates differently with each generation. For some, it is the living memory of the Revolution that brought a new dawn to Portugal, an April that forever marked the course of the nation. While for others, it is an ongoing struggle, a daily battle for gender equality and full recognition of rights. By interviewing three women of different ages, we embark on a journey through time, exploring their perspectives on freedom and the challenges faced over the decades. What remains to be accomplished regarding women’s rights? What injustices and habits remain that continue to block women’s path? For some, it was an awakening of hope, a moment when the country came together in a voice for change. They remember the climate of expectation, the seething atmosphere of transformation, where new ideals rose as pillars of a new era. For others, the 25th of April is a change told by the family and described in history books. Yet, over the years, these ideals have faced persistent challenges to gender equality. And, looking at the Portugal of today in comparison with the Portugal of the 70s, a reflection arises on the path taken and what still remains to be achieved.

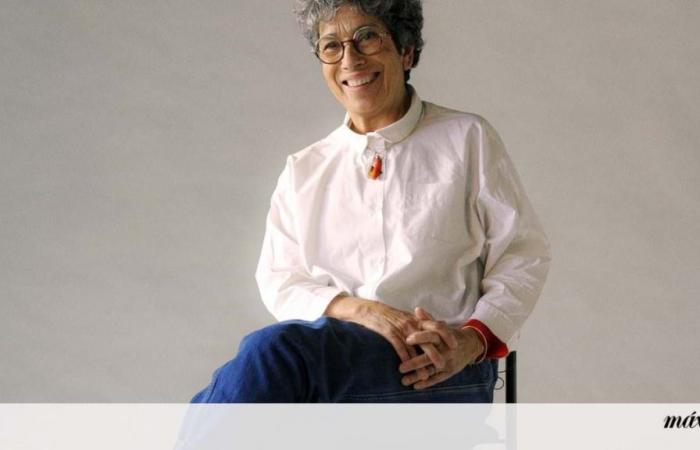

Photograph: Leonor Bettencourt Loureiro and Frances Rocha

What was life like before April 1974?

Portugal was unlivable. Everything generated fear, and fear is something that has no shape, no contours, no lines. We didn’t know if the other one was a whistleblower or not. This judicial environment [era] perpetual, continuous, was the lack of freedom. [Antes do 25 de Abril] I decided that I would go to the countries of Northern Europe, that exotic thing that was the democratic countries. Everything was already organized. In Portugal, music – pop, rock, everything – was prohibited. There was only one program, which was the In Orbit, at the end of the day. And there was only that time to go or to [nossa] home, or to someone’s home, to be able to listen. In terms of clothing, everything was subject to control. What was exotic, what was different, what was strange, and what was absolutely sought after, desired, was this “thing” that people lived in some countries… Where you could sit on the street, sit on the floor, put your shoes on grass, talking in the air, looking at the sky. None of this was viable before. We weren’t in small groups, playing games. Laughter itself was also highly censored. It was subject to censorship. All of this was absolutely unlivable. So I was leaving. When the 25th of April happens, I go to teach across the country. An extraordinary thing happens that I didn’t know what it was: walking down the street at night. This freedom was something we didn’t know.

I was 17, what happens next?

I was in my first year at university, studying Philosophy. Those who went to secondary school, those who went to high school, were only a tiny part of the population. And therefore, we were talking about a highly illiterate population. When the 25th of April happens, education is democratized, the school is open to the entire population. At that time I went to work in mechanography, a pre-computer system. I had also already taken a literacy course, with Esperança Cortesão, Agostinho da Silva’s wife. I decide to go teach, I choose to go across the country on a motorbike. As I grew up in Porto, I had this curiosity, which was very important for me. The issue of mobility, especially the mobility of a woman, was decisive. I was in the Algarve, I was in Sintra, in the Viana area, in Trás-os-Montes, and I walked around all these places. I was a teacher. It was a carrier of something that was an essential good. In addition, I had taken the literacy course. And what I did was teach people how to write. Because the biggest shame is not knowing how to read, not knowing how to sign. I gave literacy classes to the corner workers, for example, who were the ones who took care of the rumas, the roads. I was 19, 20 years old. This happened for five years. I taught the most diverse subjects for which it was necessary to teach, to people of all ages. This gave me extraordinary mobility and freedom. She was a little girl, she lived alone. And without tutoring, which is still the model of control over people and women in particular, he moved around with great ease, great freedom. When I arrived in Porto, which was my city, I found it strange. And this tutelage was strange, machismo prevailed. It is not from the 24th to the 25th of April that the way of being changes. I’ll give an example: The Movement of Things, from 1985, by Manuela Serra, one of the most notable films made in Portugal, is a film that is completely censored by its peers. It is felt that he experienced precisely this tutelage from the men who dominated at the time. And she never made any films again. Women are always erased from history, from the entire narrative, from everything. They are emanations of great rarity.

Photograph: Leonor Bettencourt Loureiro and Frances Rocha

What signs remain that this attempt still prevails?

Two weeks ago, I stopped by Imprensa Nacional and read this [pega num livro]. Report freedom. Testimonies from journalists who covered the events that occurred on the day the dictatorship ended and Portugal returned to democracy. I didn’t want to believe this title. I went in and went to buy the book. It is December 2023. Democracy is the equality of all before the law – this is what democracy does. We all have the same rights. When in 2023 our elites consider this, it is strange, it is dystopian. And this gives us the idea of what we understand by democracy. And it gives us an idea of the situation we still live in. Then, there are 20 statements, and there are only two women. One of them is Maria Antónia Palla, who at one point mentions a compliment given to her, that she “wrote like a man.” In that context, it was a compliment. But we often continue to think it is complimentary.

How do you experience this on your skin?

I, a sexagenarian, confirm by saying that this manifestation of inferiority intrinsic to women also manifests itself in that despicable machismo or in this kind, condescending, paternalistic dimension. This happens. As an administrator of two companies, I deal with clients and suppliers, and these manifestations are almost always made with loving tenderness, to which I react with irony and grace. But it’s there, you know? Age would give me authority, right? I often come home and tell my husband. ‘Look Francisco, if it were you? You’re welcome. If someone would tell you this.’ And when I tell you this, we imagine the situation, and it makes us want to laugh, it is so unthinkable. But it is the norm.

What do women still need to achieve?

There are two things here that I think are also important to say. Society, our culture, is patriarchal. Our language is patriarchal, we internalize it, we naturalize it. I’ve been wondering about flexibility at work, which is a good thing, as opposed to a rigid system. To score points, to work more hours. This discovery of flexibility comes from seeing many women working. In my companies, it was a way of being that I established. We have an economic model for producing wealth, and one of the riches is precisely the human dimension. The training of people. It’s feeling good in a place. In my companies I establish rules and operating methods that adapt to my way of being, and I usually say that I don’t want to have people who don’t have a personal life. I don’t want people who are captive to the idea that work exists outside of the other dimensions of people’s lives. The children, the parents who have to take care of… And it is in this sense that I think it is often the case that being a man or woman at the head of a company.

Credits

Realization: Leonor Bettencourt Loureiro

Photography Director: Frances Rocha

A movie of LBL team

Tags: years free Eglantina Monteiro Portugal unlivable generated fear fear form Current

--