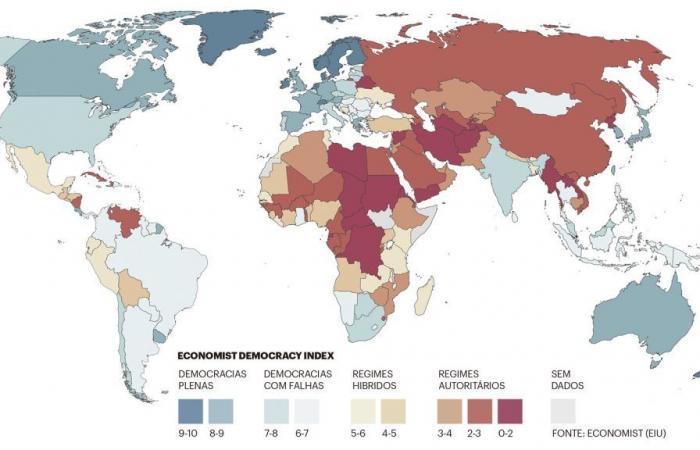

What is a democracy after all? Winston Churchill said it was “the worst form of government, except all the others”. But, as much as we appreciate the irony of the former British Prime Minister, “the power of the people”, it would be the most obvious answer, if we think about the etymology, as the word comes from the Greek we gave (people) and Kratos (power). However, is it enough to have elections for the people to exercise power? The Economist Democracy Index considers it not, and that is why several countries that have been or are going to vote this year are considered hybrid regimes, such as Mexico, or authoritarian, such as Russia. And even Portugal, which today celebrates half a century of the 25th of April Revolution, appears as a “flawed democracy”, along with other European Union countries, such as Italy and Belgium, and also the United States or India. In fact, according to the criteria of the British magazine The Economistonly 24 countries are full democracies, with Norway registering the most positive evaluation, 9.81 (10 is the maximum).

And the battle between democracies and autocracies seems to be tilting towards the latter, especially if we see it in terms of percentage of the world’s population. Another democratic index, the Varieties of Democrats, from the Swedish V-Dem Institute, points to 71% of the planet’s eight billion inhabitants living in autocratic regimes. And Freedom in the World, prepared by the Americans at Freedom House, says that 2023 was the 18th consecutive year in which the world became less free. A scenario very far from the optimism of the 1970s, when Portugal, Greece and Spain became democratic countries, of the 1980s, when giants like Brazil overthrew the military dictatorship, or of the 1990s, in which Central and Eastern Europe left of being communist and South Africa ended the racist regime of Apartheid.

“Four decades ago, the number of new democratic countries, new democratic states, states that gained independence, whether conquered or granted, states that claimed to be democratic and wanted to build democracy, were counted almost every year. Democracy was on the rise, it was on a permanent rise. Today it is in retreat. Any realistic calculations show that there are even more non-democratic or dictatorial countries than the number of democratic countries. Furthermore, and even worse, the populations living in non-democratic, anti-democratic, or dictatorial states are much larger than the populations living in truly democratic states. This is a retreat. An important setback”, sociologist António Barreto warned some time ago, in an interview with DN and TSF. And the former political exile in Switzerland, later minister in the first constitutional government, added: “democracy is currently under challenge, under threat, and has two main paths to follow: either it gives in to its adversaries and adopts policies, points of view, solutions, developments that are not democratic, and this is very serious, and can happen, or does happen sometimes; or democracy does not give in, and that does not mean war, it means not giving in to political correctness, not giving in to demagoguery, not giving in to so many things that are currently pushing for democracy to give in. We even see in countries that have shown themselves in recent decades with a real desire for democratic participation, such as the United States, countries that have tried several times to create democracy, such as countries in Latin America, Brazil, countries in Europe that a few years ago acceded to democracy, are giving in or feeling fragile within themselves, vulnerable or fragile democracies. This is a sign of great unrest, I believe.”

It is impossible not to notice in Barreto’s allusions the impact of Donald Trump’s presidency in the United States, or Jair Bolsonaro’s in Brazil, or the rise of populist right-wing or even extreme-right parties in the European Union. In America, the big question now is whether Trump will beat Joe Biden in the November 5 elections and return to the White House, and what impact his second presidency will have. In Europe, the unknown is the strength that populists and right-wing extremists will have in the European Parliament after the elections in early June in the 27 Member States. But what does this concept of “flawed democracy” really mean, following the terminology of the Economist Democracy Index, and looking specifically at the EU? A concept that is strange applied to countries like Portugal, which just a few days ago, the French historian Yves Léonard described DN as the initiator of the third wave of democratization in the world and considered it a consolidated democracy since in 1982 it extinguished the Council of the Revolution (dominated by the military) and, above all, since it joined the then EEC in 1986 and elected the first civilian president, Mário Soares.

“It is remarkable that Italy and Portugal, the two countries with which I have been linked for more than 50 years, have had such similar ratings (7.75 and 7.69). Both are classified as ‘flawed democracies’. Here are two nations that still have trouble overcoming their legacy of strong regimes. Let us not forget that the Estado Novo was inspired by the Italian fascist experience. Here we are, many decades later – and both countries affected by very low birth rates and anemic economic growth. Sleepy Italy and newly resilient Portugal. It’s not a coincidence. Basically, a lack of confidence on the part of its citizens in the future”, warns American journalist Dennis Redmont, who was a correspondent for the Associated Press in Lisbon in the mid-1960s, when Oliveira Salazar was still in power, and was even questioned by PIDE and the At one point he was forced to leave Portugal because of uncomfortable news for the regime. Later, for three decades, Redmont coordinated, from Rome, all AP information in the Mediterranean region. Today he lives in Lisbon.

“It is also instructive to read the investigation of Economist along with the famous Edelman Trust barometer, which shows that the government and the media are at the bottom of people’s trust list, far behind companies and the NGO sector. In other words, people now trust the CEOs of private companies more than than in its political leaders”, adds Redmont, who taught international journalism for more than 20 years in the Master’s Program at the University of Perugia.

“What to watch for in 2024? I would say the ‘canary in the coal mine’ is the upcoming European Freedom Act, which will be passed any day now by the EU, advocating for more transparency in government aid and regulatory initiatives through a general council for media services. First, let’s observe and see if it is not an Orwellian scheme. At least it will shed some light on more extreme cases, such as the murders in Malta, the restrictions in Hungary and individual threats in EU countries. A more slippery slope is the growing covert influence on state and private television by private and parapublic entities and the lack of self-policing by the media of individual journalists’ ‘conflicts of interest’. There are recent cases in Portugal and Italy. Also new on the horizon is the growing thirst for control of the media by the Italian right/center coalition (led by Giorgia Meloni), which is trying to transform existing defamation laws into prison sentences for journalists. In my opinion, self-congratulation is the enemy in both countries. It is also instructive that the two neighboring countries, Spain (for Portugal) and Greece for Italy, are in another category”, analyzes the American journalist. Redmont also warns: “the Portuguese and Italians would do well to pause and reflect on the reason why their societies remained imperfect. Regardless of whether we agree with the criteria of Economist. But that’s a totally different story!”

The criteria for the different indices of democracy have received various criticisms, even when they explain the enormous variety of data they collect and the complexity of the analysis. That the United States, traditionally the “leaders of the free world”, or India, “the largest democracy in the world”, are not considered full democracies, always causes some perplexity. And it doesn’t help that each index makes its own assessment, which is often dissonant. For example, if the EconomistFreedom House, V-Dem and International IDEA (transgovernmental organization, based in Sweden) all agree that Canada deserves the highest evaluation, thus being considered, respectively, “full democracy”, “free”, “liberal democracy” and “high-performance democracy”, the United States is a “flawed democracy”, “free”, “liberal democracy” and “high-performance democracy”.

“Each index has specific indicators and in the Portuguese case it seems to be the ‘government functioning’ and the lower political participation that dictate the classification. I prefer to see a good classification in freedoms, where Portuguese democracy is in good health. I confess that the factors mentioned above do not seem important to me. In fundamental terms, Portuguese democracy is well and recommended”, highlights historian and political scientist António Costa Pinto. A reading that fits well with another way of seeing the Economist index, which is the Portuguese position among the 167 countries analyzed, because if Norway is at the top and Afghanistan is at the bottom, our country appears as the 31st most democratic in the world, ahead of, for example, Italy and Belgium, but also other European countries such as Poland, Lithuania and Romania, and even South Africa, Brazil or India.

Tags: full democracies world

--